Submitted by David Jolley

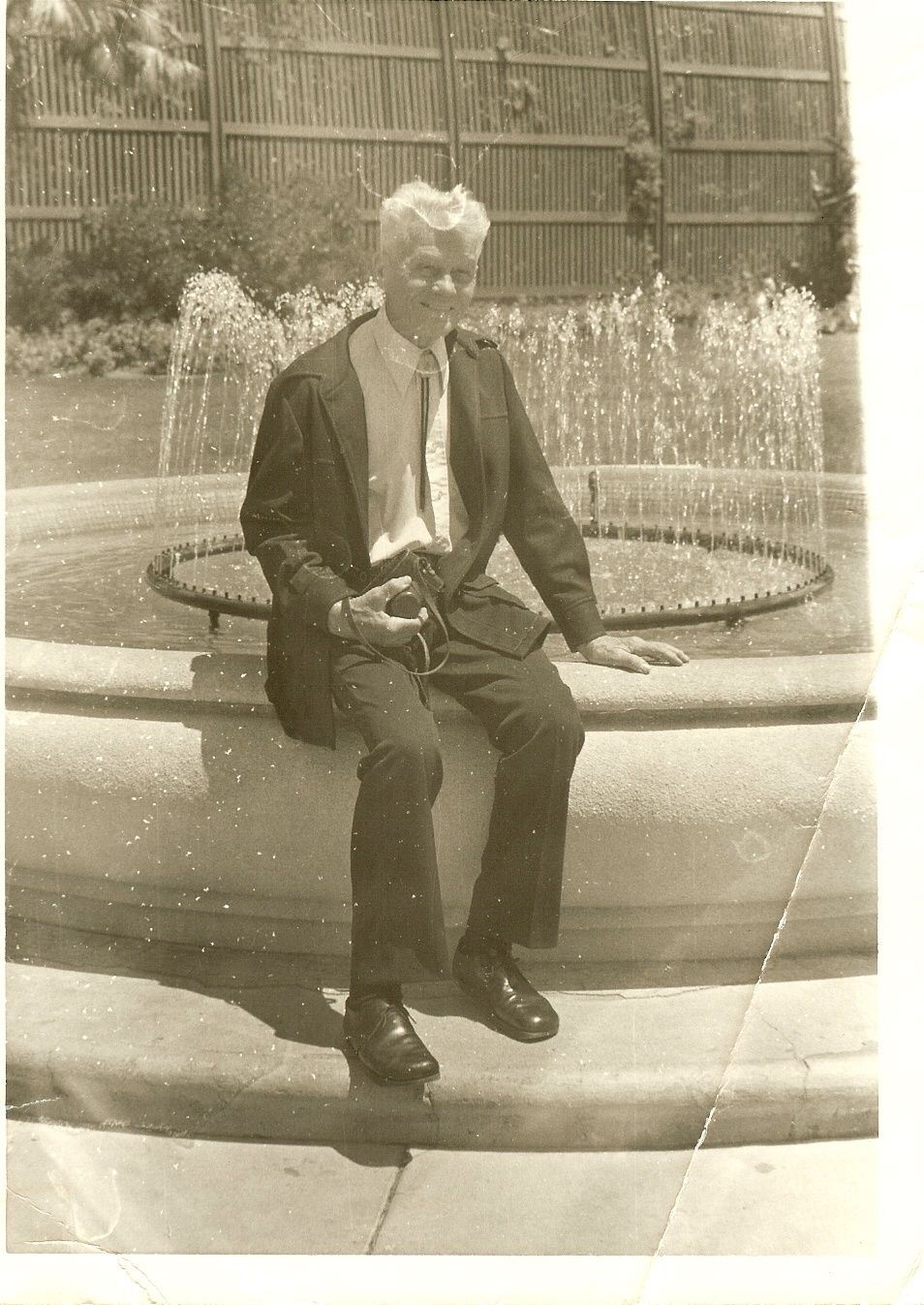

When I think back to those almost magical days of study with Mr. Hoss, the thing I always remember most strongly is the slow walk up the steps to the front door of his grotto-like house in the hills above Glendale. When I went for a lesson every couple of weeks or so, whether it was a cool winter evening or a dry summer day, the scent of the dry grass and mesquite would be in the air, and then I would hear it: the soft sound of a line of Bach Sarabande floating on the air, as Mr. Hoss played a bit before our lesson. He would play different movements, but his favorite was probably the slowest, most profound Sarabande, from the Fifth Cello Suite, the C Minor. For me, to this day, I know that to have heard him play like this is to know hornplaying itself, music at its purest and stripped to its most lovely, timeless essence. I would wait at the door for a phrase to end, or a whole piece sometimes, and then give a knock. There would be a short wait and then the door would open—slowly, yet still with a deft motion—and there he would be, erect, gently smiling, with a polite inquiry after my family on his lips. Sometimes his wife Olive would come out for a quick hello, very quick, and then we would be sitting down, getting to work….

* * *

I had begun horn at the age of 10 through the LA County School System, in 1959. My first studies were with a graduate of USC, Mr. Donald Dustin, who gave me an excellent beginning. He would come to our house to give the lessons, and I still remember him pulling up in his VW “bug”. Once I got the 1st and 3rd valve slides on my Bb Getzen reversed just before a lesson. My scales were quite a mess, which mystified me, and gave him a good laugh. Then, after about a year, through the offices of a family friend, I was able to play for and begin work with Mr. James Decker. He was an ideal teacher, and I was so fortunate to get to work with him at such a young age. I was very spoiled! He was thorough but patient, and always inspiring. He gave me the grounding in Kopprasch which I have never forgotten; and we worked in the Oscar Franz Method—my favorite (I loved the old-fashioned text, something like “The History of the World” to me…)--and the Farkas Book, which was brand-new at that time. He also had a good fatherly manner for such a young student as myself. I remember one lesson when I hadn’t practiced enough--he suggested that I should perhaps not have a lesson the following week, if I couldn’t manage to practice more. I remember feeling the loss of the privilege, and the rebuke, gentle as it was, keenly. I practiced. He was a good motivator in other ways as well. On his recommendation, I auditioned for and joined the Peter Meremblum Orchestra, one of the best training orchestras for young musicians in Los Angeles. Amazingly, now that I look back, he even suggested I drop by a recording session where Bruno Walter was recording Brahms Symphonies for Columbia Records—he himself was playing 3rd horn. I did drop by with my mother, for about ten minutes—I must have been 12 years old. Mr. Decker managed to get us into the session where we didn’t actually hear a lot of Brahms, as I remember, but we did witness a mild tirade by the great Walter. Tirade or no, it was an unforgettable experience.

One day I came in for a lesson and Mr. Decker said first thing, “Listen to this!” and put an lp on the phonograph. The playing was amazing, the arrangements were amazing--it was Billy May’s “Big Fat Brass”—so many great Hollywood players!—the brass, the HORNS—I couldn’t believe such playing. And of course, another day, he played for me one of the first pressings of “Color Contrasts,” with the LA Horn Club—more amazement, more disbelief! What motivation indeed.

As I look back now, I wonder at having the opportunity to study with such great players and teachers as Mr. Decker and Mr. Hoss. I had little or no idea at the time, really—I was just trying to keep up with the other players in Meremblum’s!! It took me years to appreciate what I had been given, to appreciate that I had truly walked a “royal road” when studying with these wonderful musicians, these fine mentors in Los Angeles.

* * *

One day, after a lesson with Mr. Decker—I had worked with him for about two years at that point--he said that there was someone he wanted me to meet. He went to the door and there stood a trim, elderly gentleman, faintly smiling. This was my first meeting with Mr. Wendell Hoss—he said hello with a dry yet musical intonation, and we talked briefly—about exactly what I don’t remember—but he was a friendly, and at the same time striking, presence from the first. I remember that. Some two weeks later, Mr. Decker informed me that he was moving to a different part of LA—down to the Long Beach area—and cutting back on his teaching and so would like me to work with Mr. Hoss. I knew he was very busy and so understood—finding time to teach a young one like me couldn’t have been easy. Still, I was very disappointed.

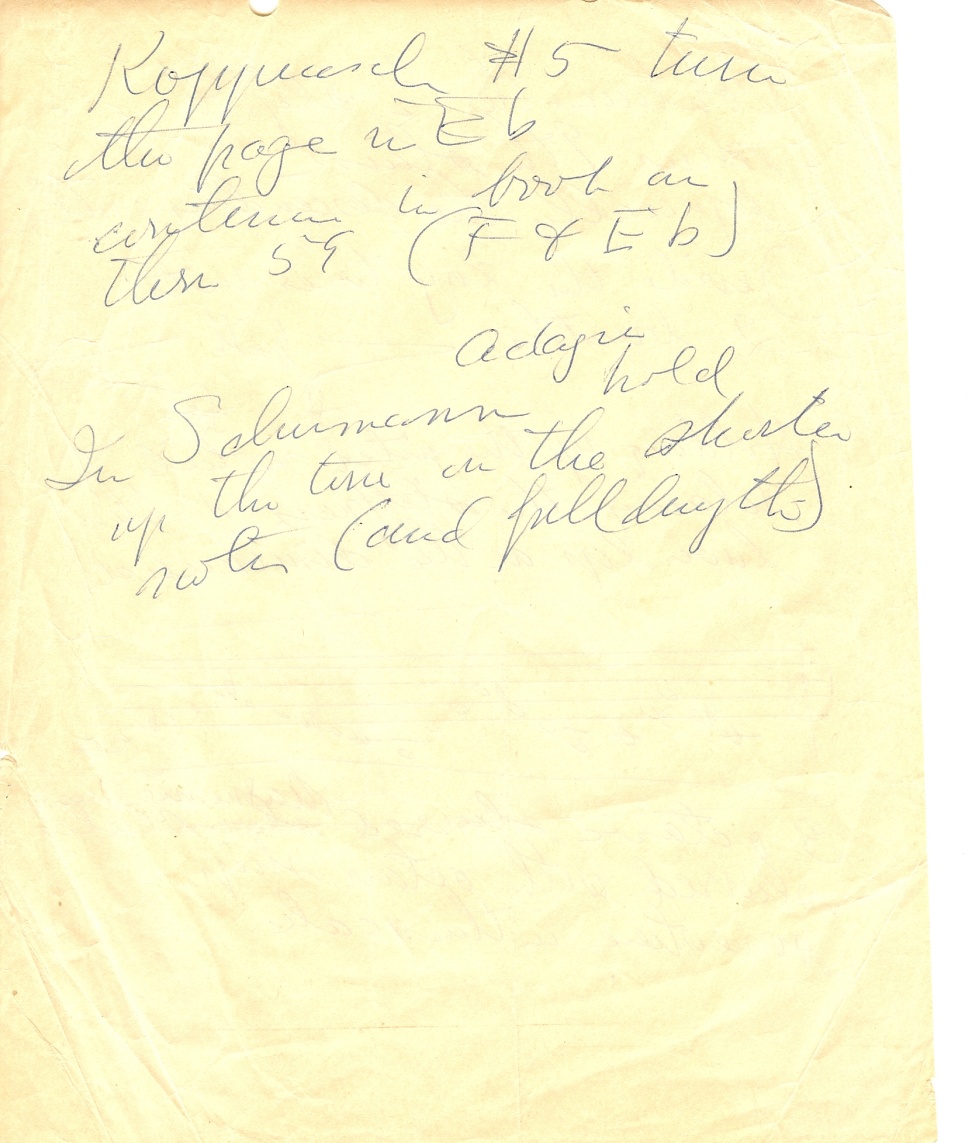

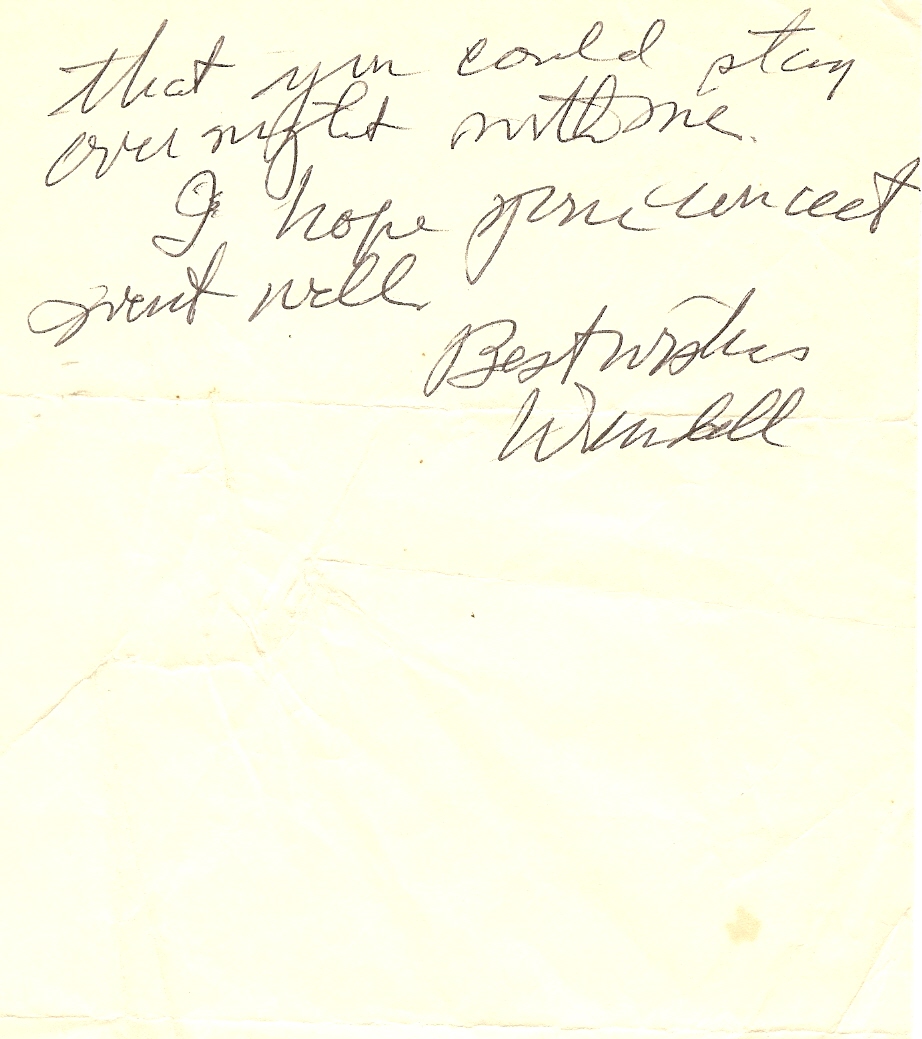

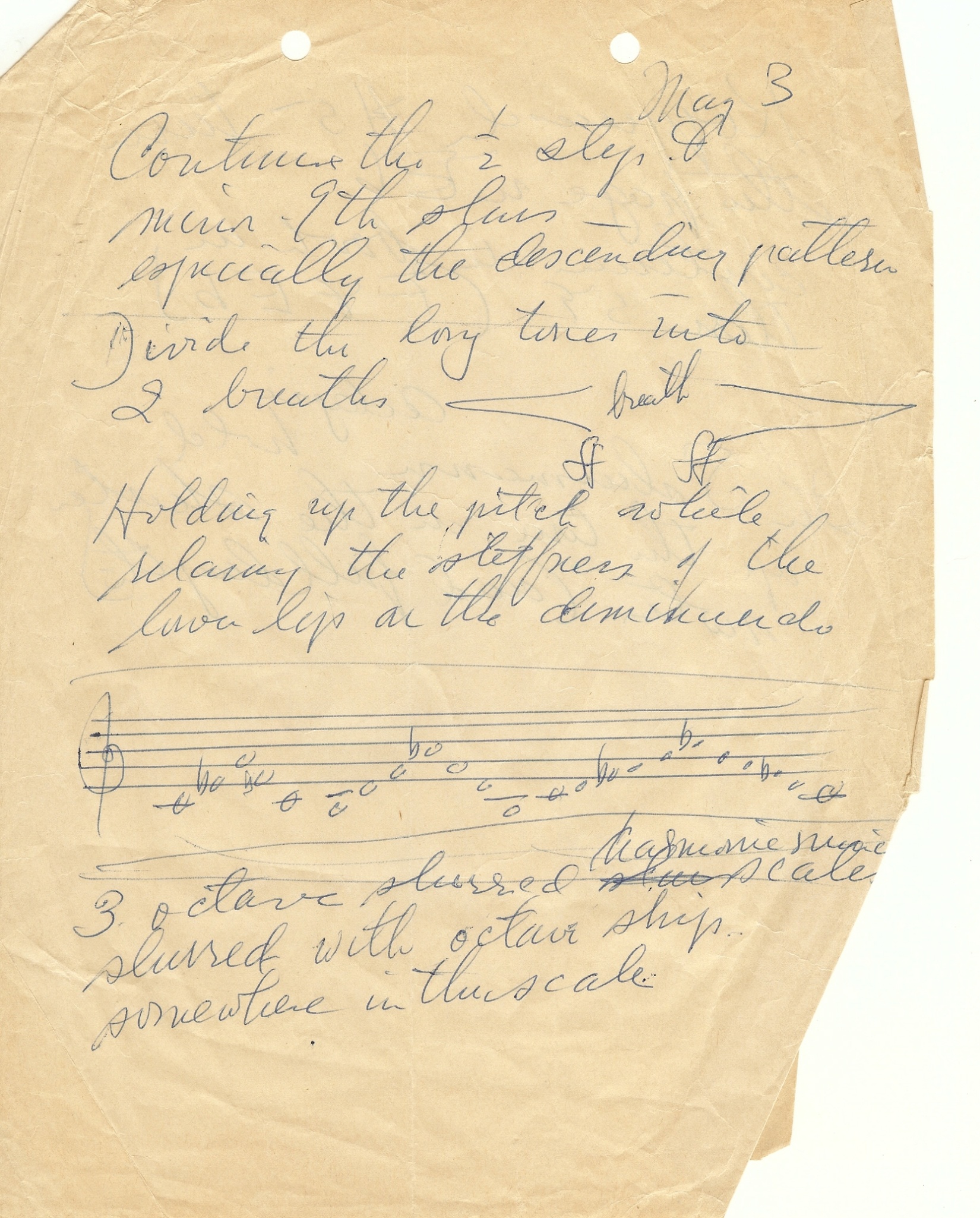

And so I went to work with Mr. Hoss; he seemed like a very nice man—and had that presence—but I really had no idea what lay ahead. It amounted to an immersion in Bach, as we worked each time on one or another of the Cello Suites, which he had famously transcribed for Horn. We also did Maxime-Alphonse and Reynolds, some solos and excerpts--and other forms of abstract work. He tried to teach me to lip trill, but I only figured that out later. I never did learn to circular breathe, though he tried to teach me that as well. I still have his lesson sheets which he would write out for me each time—(keeping a carbon copy for himself.) But in the end it is the Bach that I remember most.

Part of that memory is the very room we were sitting in. The house, now designated an historic landmark, was designed by Lloyd Wright, the son of Frank Lloyd Wright, and was built on a hillside so as to seem like it grew out of the mountain itself. The living room where we worked had an enormously high ceiling; it was irregularly shaped, but in generous proportions, with a sort of balcony—tiled with ornamental stone tiles—arcing out over part of the room. The lighting was dim, probably to help keep the house cool, and so it had the feeling of a wondrous cave, and I would sit playing my brief warm-ups before Mr. Hoss would come in.

We used to sit opposite one another, he at some distance away across the room. My assignments were usually to memorize a movement or two of the Cello Suites, along with an etude or two of Maxime-Alphonse or Reynolds. I would start with those, and he would comment or recommend some adjustment and then we would turn to Bach. Years later, I am still struck by just how extraordinary it was. For a pianist or violinist, to work on Bach is commonplace, a huge part of the training. And of course Bach is musical language itself, so that when one is working on it there is no question of getting just the technical aspect of it. Music comes first, and is always part and parcel of the technique. For many brass players today, to study Bach is accepted practice. Back then I don’t think it was quite so common. In any event, I didn’t know--I just loved it.

We worked in all the Suites, but we began with the Second, as it is probably the most accessible of the six Suites. I remember him telling me that he thought it would be a good idea—a familiar turn of phrase for him—if I would write in the chord names in each bar, so as to develop a sense of how the harmonies moved. I hadn’t had much theory at that point, but he didn’t worry about it so neither did I—and so I dove right into the majesty and the power of the wonderful Prelude to the Second Suite.

Next he talked about how the Prelude fell into three large sections, and how Bach worked with phrases of varying length—sometimes bar by bar, sometimes two bars, sometimes four or five—to build his cathedral-like structure (that’s the phrase he used.) And he talked about how to slow down or move forward according to what was going on in the harmony at each point (I had written in those chord names…). Rubato was not just a matter of playing “expressively” at any moment. It was a matter of understanding and expressing the harmonic events as they occurred. So that for instance, in bars 30-32 of the Prelude, the great activity of the harmonies meant that one would have to take a great deal of time, especially in bar 32. Other sections, like the sequence in bars 21-22, should flow more, move ahead, leading to a natural ebb and flow of the tempo. Someone today might call this a “Romantic” interpretation; but Mr. Hoss explained it to me as function of harmonic action—or the lack of action—and I have had many teachers, both of the horn and of music, but no one ever explained this vital point of music better. All of this explaining would be punctuated by our playing back and forth. I would play, and he would comment and he would also play. He would say, “you might want to try it like this…” or “you could try this”—over and over again, with endless patience.

In succeeding movements, the Allemande, the Sarabande—what I remember most is how he talked about taking time, whether for an often awkward grace note (filling in for the cello’s double-stops) or, even more importantly, for a dramatic harmony, and then how to regain the tempo. Over and over he would demonstrate “the distortion”—until I could feel how it all fit into the greater line. In the fleet Courante, he worked with me on the articulation, so that it was not a normal “brass” articulation, but somewhere between that of a horn and cello, and changing within that basic mode as well. At one point he said to me, “You might want to cultivate six or seven lengths of note—ranging from very long to staccato and everything in between.” It took me years to digest that advice, but eventually, eventually I figured it out.

In time I left for School in New York, of course. When I would come back to visit on holidays he wouldn’t give me lessons anymore. Instead we would play duets—either those from the Bach Suites—his favorites—or from the LA Horn Club Duet Book which he and colleagues were working on at that time. I still remember him and Wally Linder reading through a couple of the early ones, which I didn’t realize at the time were written by Mr. Hoss himself. Wally Linder, suggesting this change or that, would tease Mr. Hoss just a bit. For his part, Mr. Hoss, with just a touch of hauteur, perhaps, would consider a bit and then say, “No, I think not…”—and Linder would end with “Oh now, Wendell!” in his broad Mid-western accent, eyes twinkling. They were great partners in crime, those two. Playing with Mr. Hoss myself, I remember particularly the atonal ones by Adolph Weiss—at the back of the book. There is one slow one by Weiss we must have played every time I was visiting. And always his sweet, flowing tone would give me the lesson I needed, whether he called it lesson or note,and recall me from my rougher New York habits.

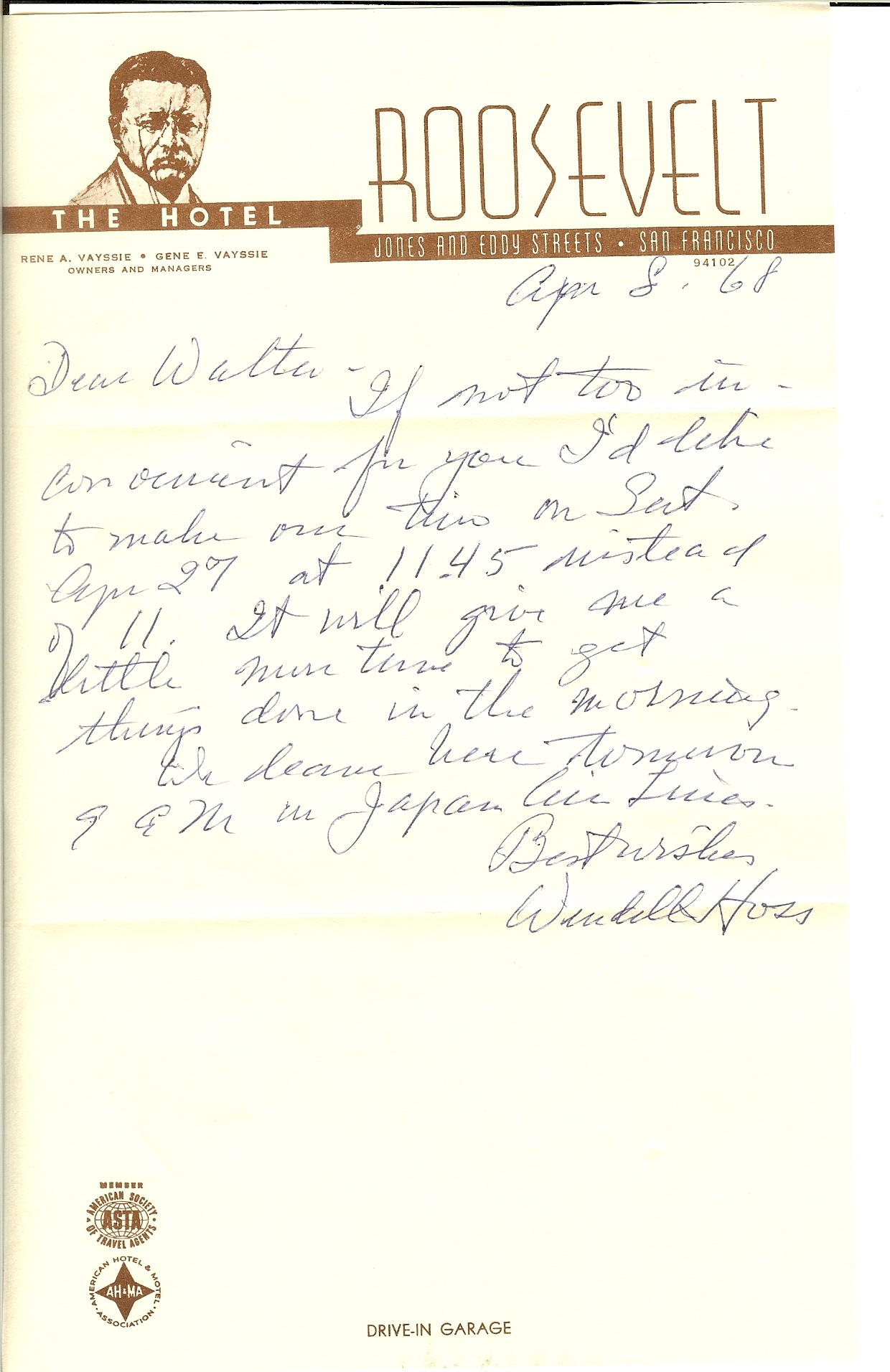

In the several years after I left for School, Mr. Hoss moved to San Diego after his wife Olive had passed away. There he was surrounded by a warm community of friends—George and Francie Cable, Lee and Larry Rogers, and others—and in the very special care of Ms. Nancy Fisch. Nancy took great, great care of him in his last years, and the others were all nearby, ready to lend support.

I have one particular memory which stands out from these years: We were sitting talking in his living room, and I was trying to learn more from him about his early career. He was tired and in pain. When I pressed him for a bit more about the early Hollywood years he suddenly pointed to the TV screen, which I had scarcely noticed was on—“That,” he said, “that’s what I was doing!”—and it was the 1932 “Mutiny on the Bounty” with Charles Laughton on the screen.

During one of my last visits to Mr. Hoss he told me that we wanted me to take one of his horns for my own. I was excited but also anxious—to have such a precious instrument handed into my care. We went into a small bedroom in the rear of the apartment and there were two horns –the 5-valve Geyer I knew so well, and another unfamiliar 5-valve—very similar design—still a Geyer, I think—but obviously not used every day—not the well-worn feel of the favorite. He told me to play a bit on both and choose one. At first I leaned towards what I deemed to be the “back-up” horn. It had a definition, a tautness, to the sound that I liked. And I really was afraid to take his own beloved instrument. But he was not approving of my choice; “No, no”—he said, “you should think it over more. I think you get really quite a special sound out of this one”—meaning his own favorite. I said it was hard to choose; maybe I could do it next time. “No, no”—he said,”you should do it now.” Heart pounding, I took the Horn. Two weeks later, Mr. Hoss passed away while I was on tour in Europe. I played the Horn for about five years after that. It was a light, light beauty. I played my first debut recitals in New York on that Horn, as well as my first solo recording.

Fifty years have passed since my first studies with Mr. Hoss. Of all the wonderful teachers and mentors I have had, and been so privileged to work with—Dustin, Decker, Chambers, Moyse, Fleisher—he is still the one, “my teacher.” When I say those words, he is the one I mean, and his sound is in my ears, and his spirit in my spirit, to this day. Thank you, Mr. Hoss—I will never forget you.